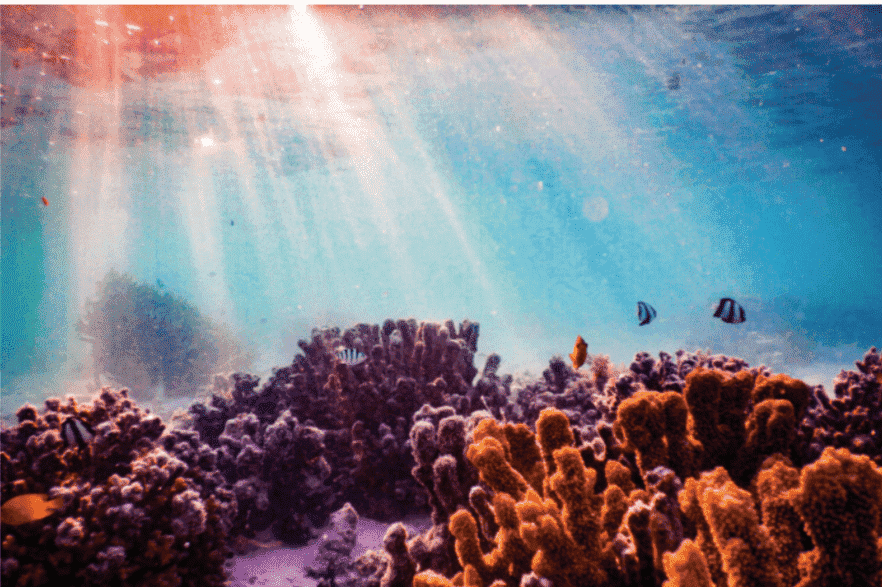

After decades of destruction and decay, a new conservation method may be a sign of hope for Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. A year after their transfer to dead reefs, the first “IVF Coral Babies” have matured and begun spawning new corals. For nearly 30 years now, the world’s largest living structure, the Great Barrier Reef, has suffered damage due to climate change and pollution. Over half of the reef has died since the 90s, a crippling loss to the marine biodiversity of the region. The UNESCO World Heritage Site is finally set to recover from the damage it has suffered over the years, all thanks to the efforts and ingenuity of the Coral IVF programme. The Great Barrier Reef, composed of over 2900 individual reefs and 900 islands, and stretching over 2300 kilometres, now has several hundred dead zones and dying reefs as a result of coral bleaching. The Coral IVF programme seeks to revitalise these damaged reefs by introducing new “baby” corals into the affected areas. They do this by collecting coral spawn from the waters and rearing the spawn into the larval stage in man-made floating nurseries. The larvae are then delivered to the damaged reefs, where they take root and grow into corals. The head of the project, Professor Peter Harrison of Southern Cross University, first began experimenting with this technique in 2016 on Heron Island. Now, the corals introduced to the reefs since then have not only survived into adulthood but are also beginning to reproduce. The coral spawn mature into larvae over the course of a week, after which they are deliv- ered to damaged reef systems either manually by divers or by specially designed robots. The most recent milestone in this journey towards the restoration of the Great Barrier Reef is the survival and maturity of the corals delivered to the reefs via the IVF process. The corals introduced by Peter Harrison and his team have recently begun to spawn sperm and eggs of their own. This is major good news, as it means that the efforts of conservationists have paid off. With any luck, it will be only a matter of time before the once vibrant reefs will be restored to their former beauty.

The process of Coral IVF is not easy by any means. Adult corals only reproduce once a year, in an event known as an “underwater snowstorm”. This is a period where the corals release sperm and eggs into the water en masse. The main issue plaguing the natural life cycle of the coral reefs is the fact that corals are dying faster than they can reproduce. Often, the coral larvae and polyps cannot survive into adulthood due to the increased water temperatures and contaminants.

The IVF project involves collecting large amounts of these sperm and egg cells from the surface of the water and transferring them into floating nursery pools. This allows the fertilisation and growth of the coral embryos to occur in a controlled environment.

10 Jan 2022

Rishab Sengupta